https://www.thoughtco.com/what-is-a-flying-buttress-4049089

The hoof as a whole is an amazing mechanism that is perfectly suited to it’s purpose. Everything on this earth that grows naturally has been engineered to it’s current form by the forces around it, and so, can be thought of using the terms of engineering. https://simplicable.com/new/material-strength

The buttress (and bar) structures serve as the lynch pin of the hoof.

Turns out, ‘lynchpin’ is very similar in meaning as ‘buttress’. Who knew…

Picture a hoof capsule without a buttress. It wouldn’t work. It doesn’t work.

When buttresses are compromised, the hoof is compromised. Full stop. Compromised being less than optimal.

And optimal buttress is more than the sum of it’s parts. Literally.

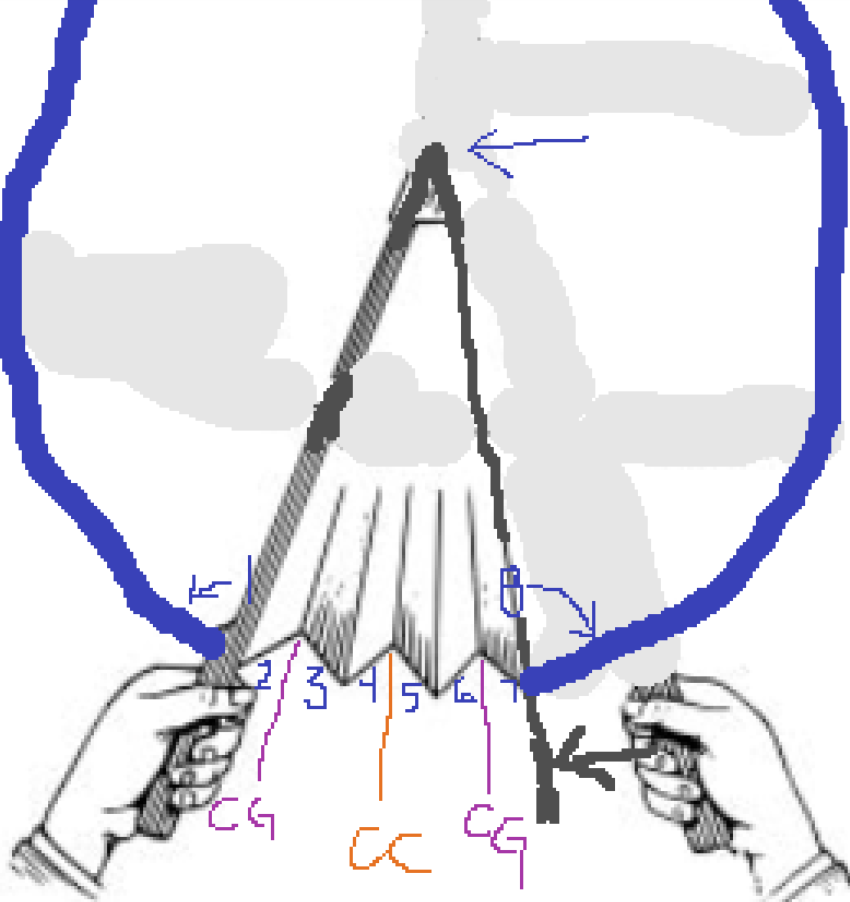

Buttress mass = Wall mass + Bar mass + (X)

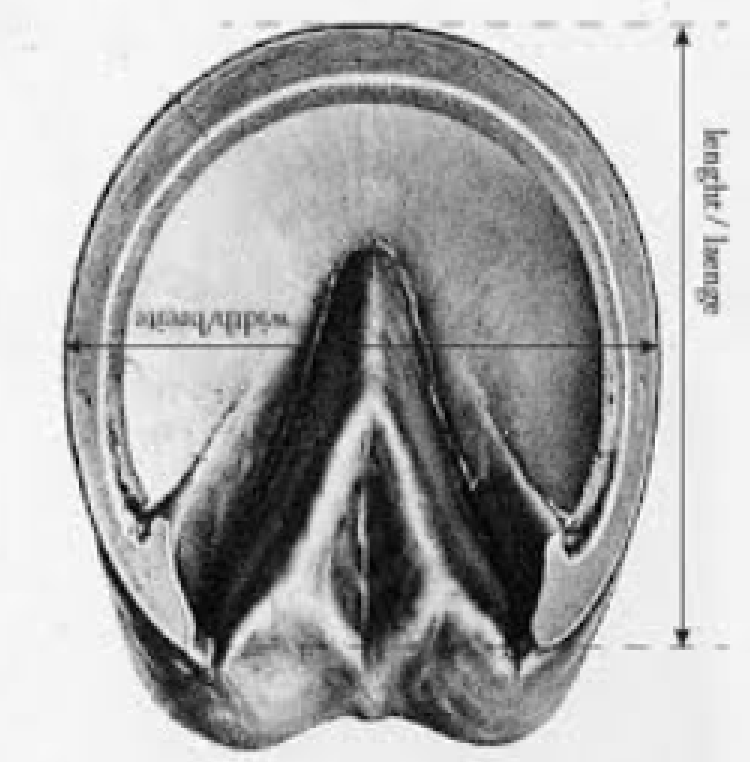

But it’s more than just that. This fortified structures hold their respective heel walls and bars at a specific angle to one another. From each buttress, the bars point back into toward the center of the capsule, to the toe quarter on the side opposite. The buttress is pointed at its outside, posterior end and the yellow laminar line makes a graceful arch around it’s interior edge.

But here’s the thing . . . It’s not always easy to see when a hoof has a compromised buttress. But, there are some tell tale signs specific to buttresses not yet being all they can be, and that there may be an issue, bearing in mind that each foot distorts in ways specific and peculiar to their own internal weaknesses and external conditions:

Thin bars ~ Thin bars can happen when the hoof is run forward from behind.

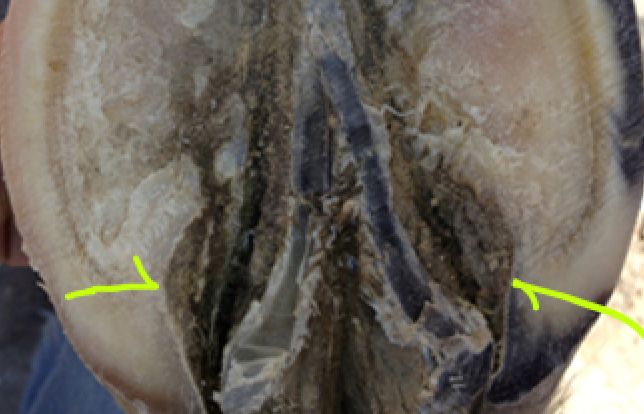

Laid over bars/bars that wont ‘stand up’ ~ Bars stand up only by virtue of their solid attachment to the buttress structure, so if they’re not solidly attached, or if the buttress structure is no longer there, the bars by virtue of the horses weight and ground forces, can only lay over.

Cracks where bar ‘joins’ buttress ~ But when there’s a crack, that’s a sign that the bar is no longer joined to the buttress. This show up as a buttress is getting trimmed out of the foot, or as the foot is being rehabbed.

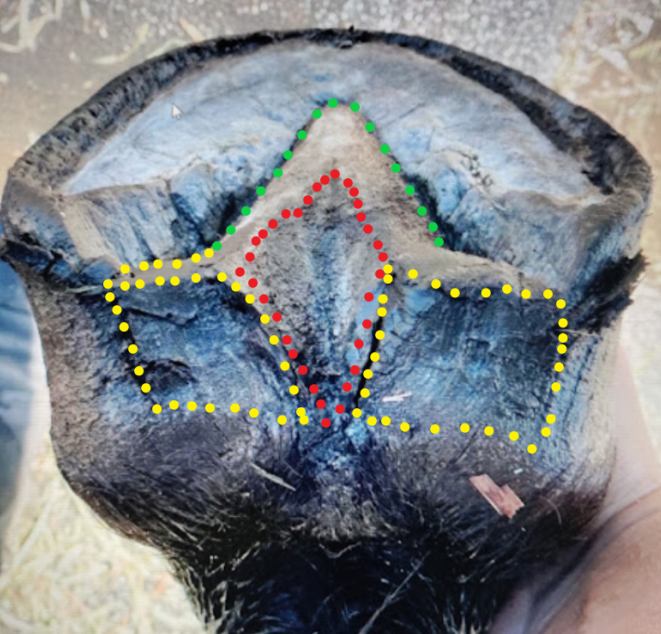

Bar abutting buttress further up the wall ~ This is the next step after a bar crack. First there’s a small dis-attachment between the bar and buttress. Then, in some feet, as the frog structures get pulled forward, the bars get pushed along forward in front of it.

Curves ~ Curved bars are a sign that the back of the foot will expand when trimmed in a way that will allow for this.

Kinks at the buttress end of bars ~ Kinks at the buttress end of bars are what happens mid way between curved bars and a dis-attached bar that is heading up the solar surface of the foot.

*Some examples below were found on the internet, not sure whom to credit.